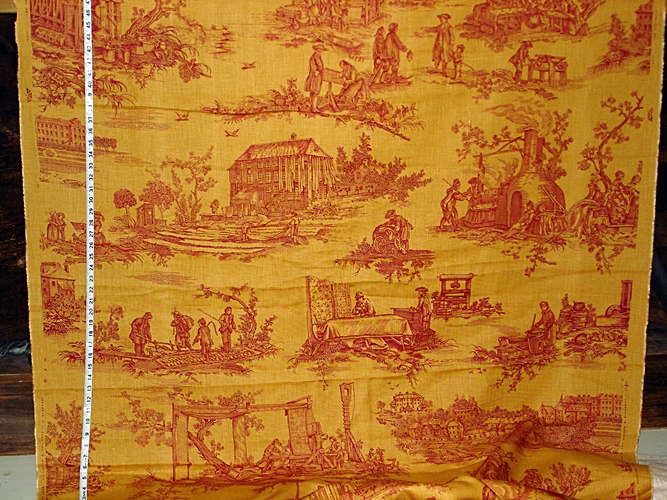

I was going through old images recently, and it was really amazing looking back at the last twenty years of toile fabrics that we have had. Virtually every company printed toiles. While some were based on the traditional French patterns, many companies developed their own patterns. I decided to dust off these patterns for people to enjoy!

But, first a bit of history! And the history of toile fabrics is a complex intertwining of politics, science, and religion.

PRINTED FABRICS REACH EUROPE

Cotton arrived in Europe around 800 AD. And colorfast fabrics were available in Europe from very early on, using natural dyes and mordants. But, it is the printed cottons from India that are the starting point for the fabrics we know as toiles.

Color fast printing had spread from India to China, Japan, Iran, and to the Ottoman Empire before the 1500’s. It then spread to Russia, the Ukraine, and eastern Europe by the early 1600’s. But, it did not spread to western Europe.

As today, fabric was prepared for printing, and then printed with the use of carved wooden blocks. The fabric could be embellished with painted details. Natural dyes were used, and fixed with mordants, so they would not run. Then the fabrics were finished.

In the 1500’s. the Ottoman Empire had developed a thriving calico printing industry, producing imitations of the popular Indian cloths. Calico fabric was not what we think of it today. It was originally a very specific type of cotton fabric, made from cotton that was not fully processed. So, it was cheap. Like many fabrics, it was named for the city in which it was originally produced. It had originated in Calicut, hence its name.

By the 1600’s textile printing had developed in Istanbul, because of the understanding of Indian dyeing practices. In 1634 Evliya Tchelebi reported that Istanbul had 25 workshops that specialized in the production of chintzes, using Indian fast dye processes. These workshops were owned by Armenians from the areas of Tokat and Sivia in NW Anatolia.

Diyuarbekir, in southwest Turkey, produced chafarcanis, a red or purple chintz with white flowers, probably an imitation of the jafracani produced in India, while Aleppo specialized in a variety of blue cotton, called ahamis.

And then, in the early 1600’s, printed cotton fabrics arrived in Europe, from India, through the port of Marseille. Marseille was one of the principal entry points for the importation of printed cottons from both India and the Ottoman Empire.

While some printing and painting of fabric was being done in Europe, it was being done with natural dyes, without mordants. Without the mordants, the dyes were not color fast. This meant the fabrics could not be washed.

Light in weight, pretty, and washable, no one could resist these Indian fabrics. They were instantly popular. Ateliers sprang up around Marseille to turn the fabrics into clothing and household furnishing. And, in India patterns were developed specifically for the European market.

The Indiennes and calicoes were not rare. Between 1670 and 1760 the English East India Company imported on average, around 15 million yards of Indian cotton cloth a year, which gives one an idea of the scope of their appeal of the fabrics and of the scope of cotton importing. And, it meant anyone could afford them. And, while undergarments made of linen had always been washable, for the first time outer garments also could be washed.

THE RELIGIOUS COMPONENT

In Europe, at this time, most countries had a state religion, which made it illegal to belong to any religion other than that of the leader of the country. Church and state were closely allied. France was allied with the Roman Catholic church. In 1517 Martin Luther, a German Catholic priest, wrote the Ninety-Five Theses, which challenged teachings of the Catholic church and the Pope. His teachings were spread quickly, due to the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press. The papacy could not suppress his ideas, and in 1521 he was excommunicated. People who followed his ideas were called Lutherans.

And this was the start of the Protestant Reformation, which plunged much of Europe into what is known as the Religious Wars. Most of northern Europe was allied with the Protestant religions, while the south remained Catholic. And to the east, the Ottoman Empire was Muslim.

Within Europe Protestant splinter groups arose, each with slightly different teachings. In France there were two main Protestant groups- those that followed Lutherans’ teachings, and those that followed John Calvin’s. The latter were called Huguenots. The Huguenots became a significant force in France. The nobility were looking to gain political strength to challenge the papacy and church, and the crown, the soldiers had been fighting for years, and the peasants were heavily taxed. All were looking for change, and the new religions were seen by many as a new start, without the corruption of the clergy.

The Huguenots, with the strength of the nobility, the soldiers, and peasants, were a challenge not just to the church, but to the political forces in power. And in 1562, after the Massacre of Vassy, the French Religious Wars erupted. While the original dissension was a religious cause, it evolved into dynastic power struggle between two families in line to the succession to the French throne. The French Religious War lasted for over thirty years.

————————

What, you ask, does this have to do with fabric? We will get to that!

————————

Henry III, King of Navarre, was one of the heirs to the French crown. He had been baptized a Catholic, but raised as a Protestant. He actually lead the Protestant army against the Royal army after the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. But, in order to have the crown reverted to Catholicism. He became King of France in 1589. In an effort to stop the fighting, and stabilize the government, he issued the Edict of Nantes. This allowed the the Huguenots religious freedom, and reinstated their civil rights. They could go to church and build schools, without persecution. And, they could belong to a guild. This was crucial to the fabric industry.

Europe spent the next fifty years dealing with social, economic, and religious changes and unrest. During this time Marseille remained a most important port for both naval and economic reasons. Cotton and printed fabrics continued to enter the country through it. And items that were made from those things were exported from it as well.

But, there was an interruption in trade between the Ottoman Empire and France. And that meant almost no cotton fabrics reached Marseille, which meant the ateliers could not supply items to their customers, both in France and abroad. To survive, the ateliers had to become fabric manufacturers.

Raw cotton had been imported from the Levant since the middle of the 1500’s and had been spun and woven into cotton since then. In 1648 calico manufacturing began in Marseille. And between 1648 and 1668 twenty print shops were in business. But, while the decline on imports from the Ottoman Empire was the impetus for the printing industry in Marseille, it was also a major factor in why it did not progress. They were also the major supplier of needed materials to do the dyeing- white cotton, madder, indigo, gum arabic, gum balls, and allum. Or in other words, the cloth to print on, the dyes, and the mordants all were imported from the Levant.

The quality of the cloth, coloring, and printing that were produced in Marseille were poor in comparison to that of both the Levant’s and India’s goods. The printers simply did not know how to do colorfast printing.

They needed to improve the quality of both the actual fabric as well as making the printed fabrics colorfast. This was especially important as relations with the Ottoman empire were beginning to improve. If the cotton printers in Marseille wanted to hold on to their business, they had to produce fabrics as good as those from India and from Asia. They needed the knowledge that was already known in the Levant. They needed the Armenian calico printers.

The Armenians were the ones who transferred the knowledge of colorfast dyeing from India to Persia to the Ottoman Empire. They were skilled in the use of madder and their fabrics were held in esteemed by Europeans and Russians.

But, then two things happened.

ENTER LOUIS XIV

1661, Attributed to Charles Le Brun

Louis XIV, the Sun King, ascended the throne in 1643, at the age of 4. His mother, who was a Catholic, ruled as regent until 1661, when he took over the government.

At this time France was in a depression, and on the brink of bankruptcy.

Enter Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Jean Baptiste Colbert was the Minister of Finances under King Louis XIV. He worked to bring France back from bankruptcy. His goals were to restore a balance of trade with countries abroad, to expand trade, and increase colonial holdings. To that end, in 1664 the French East India Company was formed- Compagnie des Indes. It was to compete with the British and Dutch East India Companies for commerce in Asia and India. The French East India Company had a monopoly on all French trade to and from the Indian Ocean. They were the only entity that could legally import cotton and cotton goods from the Ottoman Empire and India.

He also worked to regulate the guilds, one of his edicts was pointed at the textile industry. If authorities found a merchants cloth to be unsatisfactory, they were to tie him to a post, with the cloth attached to him!

And in 1669 Louis XIV made Marseille a duty free port. Not only was it a duty free port, but it was the only port that the French East India Company could use.

Louis XIV believed in the divine right of kings, absolutism, and governing from a centralized state.

In October of 1685, Louis XIV, to reinstate the divine right of kings with absolute monarchical rule, issued the Edict of Fontainebleau, which revoked the Edict of Nantes. The Protestants were forced to convert to Catholicism or flee the country. Other countries welcomed the Protestants. Many even set them up with homes, jobs, and money.

Many textile workers were Protestants, who fled the country. So, France lost a good portion of the workers who had knowledge that was important to the textile industry. And, that expertise was gained by other countries. The countries the Huguenots immigrated to gained all the technical knowledge the workers had, while France lost it. This was a huge loss to the French textile industry, as well as many other industries.

And then, a year later, in 1686, Louis XIV banned the importation of cotton and printed cotton. The silk, linen, and woolen mills were going bankrupt due to the importation of cotton. To protect those industries, and bolster exports of their own silk textiles, the importing of cotton and silk had to be stopped. The French East India Company could import cotton for re-export only.

_____________________

England also banned importing of cotton in 1702. But allowed it continue to be made for export. This meant that the printing of textile industries there continued to expand, while Frances’ did not.

______________________

So, the ateliers that made cotton items were suddenly out of a job. To get around the ban, many of the Ateliers moved from Marseille to Comtat Venaissin, an area that surrounded Avignon, which was under Papal control, and thus not a part of France. In 1726 France made it illegal to wear any of the cotton fabrics. And, severe penalties were added for helping the importing or manufacture of the goods. In 1734, a concordat was signed between the Pope and Louis XV, submitting the Comtat Venaissin to the same law. The factories in Avignon then also closed.

But, because the French East India Company imported the goods into Marseille, they actually were on French soil, for both auctioning and re-exporting. Even though the ban was extended to wearing of printed cottons or using them for furnishings, the ban was impossible to enforce. And the smuggled goods remained popular. And in the late 1600’s restrictions relaxed enough in Marseille that it again became a center for printing.

One of the problems was the knowledge of how to do colorfast printing was not known.

The French East India Company sent people to try to find out the secrets of the dyeing process. And it was determined, over time, that the colors and dye fastness ere due to natural things- dye plants, mordants, and the actual water used.

One of the people who sent back valuable information on dyeing was Father Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux ( born.1691, died 1779 ), a French Jesuit priest, a missionary in southern India. His converts gave him information on the preparation of cotton for dying, as well as the dye process, and the finishing of the fabric, which he passed on.

But, even though Coeurdoux sent back detailed information, the practice of colorfast printing of cotton needed experienced printers to show how it was done. The Armenians were experienced in the art of dyeing, and were key to the development of printing of colorfast cotton in Europe. They had knowledge of how to print colorfast fabric that could not be conveyed by written information.

Armenian dyers and fabric makers came to Marseille to take advantage of Marseilles’ free port status, in an attempt to compete with the imported goods. In 1672 two Armenians came to Marseille, to start a printing textile company. And in 1677. the first calico printer was set up in Avignon. Printing continued during the ban, in cities that were not directly administered by the central government, and later in the Arsenal in Paris, Nantes, Angers, and Rouen. As early as 1744, Jean-Rodolphe Wetter had opened workshops in Marseille, a free port, where he employed 700 workers and excellent draftsmen recruited from the local Painting Academy. The brothers François and Thomas-René Danton had established themselves in Angers in 1752. Louis Langevin had opened an establishment in Nantes in 1758, and Abraham Frey in Notre-Dame-de-Bondeville, near Rouen in 1756. Other workshops operated in Lorraine, in Barrois, in the city of Montélimart, in the Comtat Venaissin, papal land, and especially in the small republic of Mulhouse, where Koechlin, Schmaltzer and Dollfus had founded in 1746 the famous factory known as “the Court of Lorraine “.

But colorfast dyeing and printing still were not that developed. While colorfast printing of cotton could be done in Europe by 1670, the techniques for doing so were still the same as those used In India. The designs were added to fabric by painting on it, printing with wooden blocks, and also by the use of wax resist. Each color needed its own block. Printing with engraved copper plates was developed in Ireland in 1752. The engraved plates allowed for finer detail than the wooden blocks, but again, each color needed its own plate. These were all time consuming methods of adding pattern to fabric. With the popularity of the cotton fabrics, these were not techniques that Europeans wanted to use. They wanted faster production methods.

LOUIS XV

Louis XV was responsible for several components of the advancement of the French textile industry. In 1715, at the age of twelve, Louis XV became the king of France, and sat on the throne until his death in 1774. From 1715- 1723, he had a regent, Phillippe II, Duke of Orleans. Phillippe II was not interested in pursuing the persecution of Protestants. Though the laws were not changed, gradually the application of them relaxed. And the Protestants were allowed some religious freedom.

His mistress was Madame de Pompadour. Madame de Pompadour was a patron of the arts, and had huge political influence. She not only wore Indiennes during the ban, she also decorated her rooms with them. It is said she is partially responsible for the lifting of the ban on printed fabrics, and the printing of them.

In 1740, the ban was loosened slightly when the government decided to allow resist-dyed indigo fabrics to be produced.

In an effort to promote free trade, to expand the French textile industry, which could print fabrics for sale if allowed, the ban and all restrictions of the importation of printed cottons, and the production of them was lifted in November, 1759.

ENTER CHRISTROPHER-PHILIPPE OBERKAMPF

the father of toile.

________________________________________________________________________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

https://books.google.com/books?id=6BON6WWKIt4C&pg=PA170&lpg=PA170&dq=armenian+print+shops+marseille&source=bl&ots=jyqhAkjg34&sig=ACfU3U2toDyqRW9Er_Pb5UAnDAAfPKvirg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjwoaCevM3gAhWidN8KHVmSCW0Q6AEwAXoECAYQAQ#v=onepage&q=armenian%20print%20shops%20marseille&f=false

https://networks.h-net.org/node/22055/reviews/151850/farooqui-gottman-global-trade-smuggling-and-making-economic-liberalism

When Cotton was Banned: Indian Cotton Textiles in Early Modern England

http://www.diptyqueparis-memento.com/en/indian-cottons/

https://books.google.com/books?id=6BON6WWKIt4C&pg=PA170&lpg=PA170&dq=armenians+marseille+cotton&source=bl&ots=jypqzhmi33&sig=ACfU3U0k1yQVQQa5fXejiVlMgsC6hL-gSQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjljM3J1qzgAhUHxVkKHfs5C7wQ6AEwEnoECAEQAQ#v=onepage&q=armenians%20marseille%20cotton&f=true

https://reason.com/archives/2018/06/25/before-drug-prohibition-there/print

http://www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/Research/GEHN/Helsinki/HELSINKISouza.pdf

https://www.tdjifoundation.org/christophe-oberkampf

https://books.google.com/books?id=N2x2BgAAQBAJ&pg=PA194&lpg=PA194&dq=Koechlin-Dolfuss+printing+factory+in+Mulhouse,&source=bl&ots=AAE6ZYC5Ip&sig=ACfU3U29YRN9sl7smJI9LpbVEzp7MPCsQA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiR3PWehKrgAhVkQt8KHYWJDEgQ6AEwBHoECAcQAQ#v=onepage&q=Koechlin-Dolfuss%20printing%20factory%20in%20Mulhouse%2C&f=false

www.https://www.francetoday.com/culture/made_in_france/made-france-la-toile-de-jouy/

http://www.guide-tourisme-france.com/VISITER/musee-toile-jouy–chateau-eglantine–jouy-josas-17247.htm

https://www.cotton.org/pubs/cottoncounts/story/

https://www.tikitours.com.au/enews/2015/4/22/the-surprising-history-of-provencal-textiles

http://paintandpattern.com/indienne-textiles/

http://www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/Research/GEHN/Helsinki/HELSINKISouza.pdf

http://paintandpattern.com/indienne-textiles/

When Cotton was Banned: Indian Cotton Textiles in Early Modern England

https://www.tdjifoundation.org/single-post/2017/09/25/The-amazing-tale-of-Christophe-Phillipe-Oberkampf

http://www.jouy-en-josas-tourisme.fr/iso_album/circuit_1_mars_2016.pdf

http://www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/Research/GEHN/Helsinki/HELSINKISouza.pdf

http://epicworldhistory.blogspot.com/2012/06/french-east-india-company.html

http://www.french-treasures.com/historical.htm

https://reason.com/archives/2018/06/25/before-drug-prohibition-there/print

https://www.tikitours.com.au/enews/2015/4/22/the-surprising-history-of-provencal-textiles

http://www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/Research/GEHN/Helsinki/HELSINKISouza.pdf

https://networks.h-net.org/node/22055/reviews/151850/farooqui-gottman-global-trade-smuggling-and-making-economic-liberalism

https://books.google.com/books?id=SqF3jnPcyOYC&pg=PA294&lpg=PA294&dq=textile+printing+benoit+ganteaume+jacque+baville&source=bl&ots=5ex_TolhbF&sig=ACfU3U2–EWVWuVCxGAkE7TZs5WVJGCXng&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjV8cinoITgAhUGd98KHQhlCOcQ6AEwCXoECAEQAQ#v=onepage&q=textile%20printing%20benoit%20ganteaume%20jacque%20baville&f=false

History of the Jouy factory and printed canvas in France. TEXT / Henri Clouzot